Mirela Gjata was not in the habit of checking herself for symptoms of illness. "Poverty does not allow us to have health care," she said. The 58-year-old woman is a member of the Egyptian community in the central Albanian city of Berat. Just as the Roma communities, the Egyptians have faced widespread discrimination that has made it difficult to access basic services like health care and education.

But since 2019, UNFPA has been working with the Albanian government and partners to develop and support a programme that focuses on reaching out to these marginalized and vulnerable groups through volunteer health mediators to promote better awareness and equal access to medical care and social services.

Health mediators host community-based sessions with girls and women from minority communities to tell them more about the various health risks they might face and how they can detect symptoms at an early stage. It was through one of these community sessions that Ms. Gjata learned about how to look for signs of breast cancer. She performed a self-examination and discovered lumps in her breast.

The UNFPA health mediator team was also there to guide Ms. Gjata through the medical process. They helped her first get tests to confirm her cancer diagnosis, then began procedures for her to go to the capital, Tirana, for specialized treatment and surgery. Ms. Gjata is now cancer-free and continues to receive support from her health mediator for follow-up care.

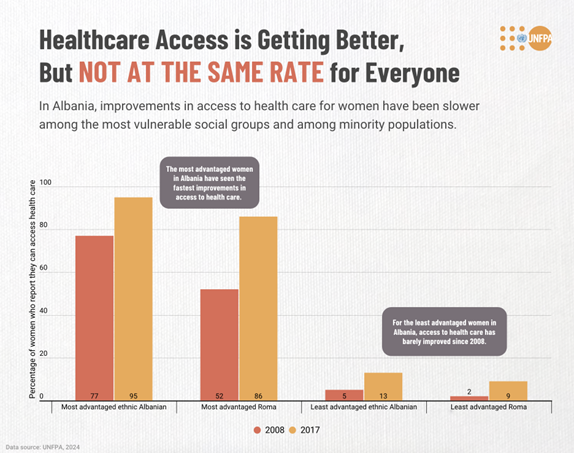

Access to health care for women in Albania has been getting better in recent years, but not everyone has seen improvements at the same rate. From 2008 to 2017, according to Demographic and Health Survey data, the biggest gains were among the most advantaged women. Meanwhile, women from the least advantaged backgrounds have barely seen any change. Among the least advantaged Roma and Egyptian women – like Ms. Gjata -- only 9 per cent reported that they did not face serious problems in accessing health care, at the time of the latest survey in 2017.

Grisel Zenuni, 33, is one of the health mediators working to make sure health care access improves for everyone.

"It is not easy to gain trust among vulnerable communities,” he said. But having roots in the Egyptian community himself, his first-hand understanding of the people has helped him better serve their needs, “I strive to help, facilitate, and guide individuals who face health problems or who need support and guidance to access every level of care, so they don't waste time, spend money, on something that can be resolved and is possible to resolve for free, without delays and without obstacles.”

UNFPA has now trained more than 100 health mediators from the Roma and Egyptian communities in the districts of Berat, Tirana, Korça, Elbasan and Shkodra. Between 2019 and 2022, these mediators assisted more than 4,000 people, including people with disabilities, young people with higher risk of HIV, older people and pregnant women.

While there have been successes, Mr. Zenuni says, “our work as health mediators does not stop." In recent years, as a result of UNFPA’s work to increase access to screening services for women of Roma and Egyptian communities, there has been a significant increase in the cases of women diagnosed with breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer is the second most-common cause of cancer death among reproductive-age women in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Albania’s Ministry of Health and Social Protection and Institute of Public Health estimates that between 2,000 and 3,000 healthy years are lost to cervical cancer every year in Albania, costing the country US$6 million annually in lost productivity and cost to the health care system.

Screening programmes can reduce cervical cancer rates by up to 80 per cent or by up to 90 per cent if combined with the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination of adolescent girls. In 2019, the Government of Albania with support from UNFPA established the country’s first cervical cancer screening programme targeting women between 40 and 50 years old.

So far, 52,000 women have been screened.

Mr. Zenuni said health mediators are trying to make sure vulnerable communities are included in these screening efforts: "We talk to girls and women about the importance of testing for cervical cancer and for breast cancer and we provide essential information that enables women to perform self-examinations to look for lumps, for example.”

And as a cancer survivor, Ms. Gjata knows the importance of health mediators and their work toward improving equal access to health care services for the most vulnerable and marginalized. "If it were for me, I would not have been treated for breast cancer,” she said. “The team of mediators helped me to access all the services I needed and and, as a result, to be alive today. After what I went through, I tell every woman in my community, whenever I can, to prioritize their health.”